REARTIKULACIJA #10, 11, 12, 13, 2010, Marisa Lobo, Intervention

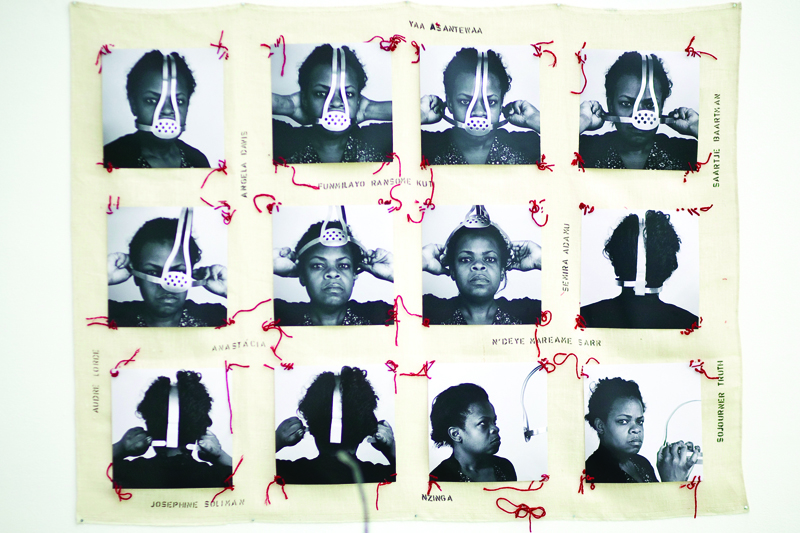

Iron Mask, White Torture, performance and installation, conceived by Marissa Lôbo, 2010

Iron Mask, White Torture, performance and installation, conceived by Marissa Lôbo, 2010. Iron Mask, White Torture was presented at the group exhibition “Where do we go from here?” at Secession, Vienna, 2010. Perfomers: Agnes Achola, Alessandra Klimpel, Belinda Kazeem, Flavia Inkiru, Grace Latigo, Steaze, Sheri Avraham, Njideka Stephanie Iroh, Marissa Lôbo. Photos Performance installation: Ana Paula Franco. Photos from Secession: Mario Heuschober. Editing film: Annalisa Cannito. Photo Documentation: Susi Krautgartner. Coordination access photo material: Catrin Seefranz.

Short report from the performance Iron Mask, White Torture, conceived by Marissa Lôbo. Report by Collective of Black Women Subjects in Art Space, written by Marissa Lôbo and Sheri Avraham. Date of the performance: July 2, 2010, time: 19.30, space: Secession, Vienna.

THE SPACE: A MUSEUM

A space of epistemological violence production. Appropriation of the history of the “other,” a constant reproduction of the White Western desire of exposing and determining the otherness, the pure empire of Voyeurisms.

INTRO Time 1 at 18:59

Nine black women and women of colour, with black outfits and bright blue eyes, are spread out in the exhibition space, observing the artwork amongst the spectators. Their presence and their homogeneous appearance cannot be ignored. The occupation has started. The nine women’s costumes symbolize two important anchor points in the history of black resistance.

Their black outfits give tribute to the Black Panther Party, expressing their importance as a significant resistance group in all of black history. The second aspect can be discovered through the bright blue contact lenses, as they relate to the blue eyes of Anastácia, who was enslaved, and because of her struggle for freedom, becomes a symbol for colonial resistance.

PRESENTATION Time 2 at 19:27

The curator presents the title of the exhibition, “Where do we go from here?”. She makes reference to Martin Luther King, Jr., who originally proposed this question. “Where do we go from here, Vienna?” – isn’t this such an ironic question to ask when your history is imprinted in every corner, and at the same time we revile openly and legally a deep-rooted racist structure, as for example, in the election campaign, or as it is defined by the legislature enforcing “Alien Laws.” In the gallery space, the loud noise from the audience swallows the voice of the curator in her attempt to carry an opening speech. Some, more devoted to the ritual than others, surround her with the honest intention to hear. The rest wobble around, waiting for the bar to open its hatch, disregarding the curator’s intention. This particular scenario is not different from any of the other Gallery / Museum / Art Space openings that take place in Vienna. The same artists, curators and mainstream media are here again in a celebration of the white territory. Praising their visual gaze regimes of exclusion of otherness. “Where do we go from here?” – is an exhibition where the other is invited as a guest to present his/her work and then is being asked: where do you go from here?

THE PERFORMANCE Time 3 at 19:34

One long, empty table slowly gets occupied with nine black women and women of colour. They sit next to each other and stare directly at the audience. Their blue eyes appear very clearly as an element that has been shoved into the black subject body. This physical illustration is meant to evoke a certain dissonance within the viewer – a white middle- and upper-class – the typical guest of such an event. For a moment, he has been disturbed in his ritual and is compelled to witness such a gaze upon him. Nine different women with different backgrounds are telling the same story through their blue-eyed gaze. The story consists of a mask and its physical form that have been created and constantly revised in order to enforce the white male supremacist. They are re-telling the history, but now from a different body. Thus, the female black body tells the history of suppressions and mutations.

THE FINAL CUT Time 4 until 20:05

Sitting at the table the group has started to prepare a genealogical critique, they create a moment for ignoring the white canon that is legitimized by knowledge produced by Western or Eurocentric epistemologies. With this mask, the colonizer tried to silent the black subject. The group articulates and gives voice to all objects exhibited in art museums that have been an object of theft, violence, lies and silence. The reading starts with a repetition of the name Anastácia by each of the nine performers. Then each woman, one after the other, exposes firmly thoughts by black feminists. Thoughts that concern racism and sexism, Africa Diasporas, black identities and colonization are juxtaposed with critical migration politics and “rethinking black feminism as a social justice project. This develops a complex notion of empowerment, shifting the analysis toward investigating how the matrix of domination is structured along certain axes – race, gender, class, sexuality and nation” (as Patricia Hill Collins says in “Black Feminist Thought”). The mask of silence is broken with each of the quotations.

“There is a mask of which I heard many times during my childhood. […] Formally the mask was used by white masters,” – is the first sentence uttered by the performers. It is from Grada Kilomba. It is striking; it is like an echo (THERE IS A MASK, THERE IS A MASK, THERE IS A MASK). Quotes from important black women theoreticians that are read in the intervention-performance are here to reinforce black feminist struggles that have taken place as a collective voice and for reconceptualising the definition of knowledge.

In the last minute of the performance, they take the Blue Eyes out, they leave the space and some applause comes from the audience. This is a violent moment of contemplation on the art work, and the strong voice by Grace Latigo asks: “ Is there something to be applauded here?”

Not to forget the question that doesn’t want to be silent: “Where do we go from here?”

Nowhere! – We are here to stay!

*Texts quoted in the performance are by bell hooks, Grada Kilomba, Patricia Hill Collins, Araba Evelyn Johnston-Arthur, Belinda Kazeem, Claudia Unterweger, Njideka Stephanie Iroh and Grace Latigo.

*foto: Iron Mask, White Torture, performance and installation

*foto: Iron Mask, White Torture, performance and installation

THE MANY ANASTÁCIAS

Legend has it that Anastácia was a blue-eyed Bantu, enslaved and transported to Brazil and forced into silence by her owners with an iron gag. There are various reasons for this brutal form of punishment, depending on the perspective it is viewed from. One significant version places the iron mask as vengeance for resisting sexual exploitation by the so-called “master” of enslaved Africans; another portrays the mask as punishment for Anastácia’s political disobedience as she joined a Quilombola, a resistance movement of runaway enslaved Africans.

The metal mask represents several sadistic aspects of colonialism within which violence is notoriously legitimized through the brutal desire of a white man for the sexualized and de-subjectivized Black body. This ambivalent imago goes beyond the image of a victim of colonial violence and represents the fighters who refuse to be silenced. With the iron mask and her unbroken look, she is read as the rebellious subaltern that is forced into silence – or not? But what is Anastácia keeping silent?

The adoration of holy Anastácia is profoundly popular in Latin America and multifaceted, but she never reached the official status of saint (the Catholic Church declared her to be non-existent in 1987). She is worshipped as a rebel and a fighter for the movement of enslaved Africans, as a Black woman who resisted against the sexual violence/power of the so-called “master,” as a martyred innocent servant of God.

The “Movimento Negro” of Brazil refuses to recognize Anastácia as a Black icon because the cult surrounding her comes from Catholicism, which had strong ties with the colonial authority and transformed enslavement into the symbolic authority/power of missionary work. Worshipping Anastácia, who had her torturers’ blue eyes and was forced into silence, would redeem the oppressor and not the oppressed.

The many faces of Anastácia make the indissoluble ambivalence of this imago clear: it is the Black woman who was not obedient, who did not listen to orders, who was enslaved, but with the face of the warriors, who stares balefully and relentlessly, who was forced into silence and screamed incessantly: I am not a slave.

Anastácia’s Bluest Eyes

In her book “The Bluest Eye,” Toni Morrison undertakes a poetical critique of the dominant ideal of beauty, which white supremacy transfers into the fantasies of the ideal body. The desire for blue eyes is the effect of internalised racism, created by colonialism and which entrenches itself as trauma in the unconsciousness of the Black subject. The dream of blue eyes obscures the view of Black identity. Anastácia’s striking “bluest eyes” tell the story of distorted desire and of symbolic and sexual violence/power through the white colonial ruler. The colonial ruler appropriates the Black body and instrumentalizes it as an exotic object of desire, which the hyper-sexualized Black woman must serve as. Anastácia pays for her resistance against this violence/power by being tortured with the metal mask, which leaves her eyes visible; a blue that mirrors desire pervaded by racism.

The Mask of Silence

Anastácia was sentenced to speechlessness, a form of punishment notoriously administered by the regime of enslavement, a system marked by sadistic excesses of violence, which are repeated and perpetuated in today’s society, a society characterized by structural racism.

“The mask represents, in this sense, colonialism as a whole: Why must the mouth of the Black subject be fastened? Why must she or he become silent? What could the Black subject say if her or his mouth were not sealed? And what would the white subject have to listen to? In other words, who can speak? What happens when those who were forced to be silent start speaking? And above all, what can we speak about?” (Grada Kilomba)

A Critical Genealogy

Anastácia with the metal mask is a figure from the sinister times of the regime of enslavement that degenerated to the melodramatic subject and motive of rhetorical outrage. She is a figure of the present. The racist and sexist power relations she embodies are omnipresent. Anastácia, Josefine Soliman, the names remain hidden.

“In a culture of domination, preoccupation with victimage is inevitable.” (bell hooks) But the history of Black resistance and its protagonists remains just as hidden.

What does Anastácia say if one places her beyond worship and condemnation into a critical genealogy that Black theorists have been working on for decades? Does one place her in “a class of women and people of color” as someone who asserts oneself and puts up resistance between theory and practice? Does one place her in a new context of re-figuration of Black history through the production of knowledge from activist practice? So is Anastácia talking about the possibility of resistance, as bell hooks stated: “Even the most subjected person has moments of rage and resentment so intense that they respond, they act against. There is an inner uprising that leads to rebellion, however short-lived. It may be only momentary but it takes place. That space within oneself where resistance is possible remains.”

This Anastácia resists against the symbolic power of being a victim, an object, an object in a museum, a saint. She has the penetrative glare of someone who sees and in doing so focuses on colonialism and its perpetrators.

Marisa Lôbo, activist, member of the autonomous organization for women migrants, maiz, Linz; studies Post-Conceptual Art Practices at the Academy for Fine Arts in Vienna.

Translation from German by Njideka Stephanie Iroh.

Iron Mask, White Torture, installation